my languages remember me as someone else

speaking in tongues & smiling with dimples

I once knew and loved a boy whose first language was Arabic. We would trade sounds in each other’s languages that our tongues have never been taught to make, pressing our fingertips to each other’s throats to feel a fluttering pulse as we tried anyway.

I say ड़ in Hindi [the closest sound in English is allegedly r. Linguists call it a voiced retroflexed plosive, or ɖ ], enunciating slowly the way you would for a child. The sound itself isn’t that stretchable, it is sharp and taut like an overdrawn bow-string. I hold it for as long as I can and then let it go, hard and true. It flies like an arrow and in the wind trail I feel the ghost of all the words I could say with it nestled in, the slang I wonder if I am using correctly, the surety of sound that erases the accent from the years spent out of India.

I feel his Adam’s apple jumping against my palm as he tries to chase the sound but he doesn’t pull tight enough, does not let go hard enough. It doesn’t sound quite right and I tell him that. I am only joking but I am looking at him with an eagerness and expectation that doesn’t match my tone.

He retorts by saying عin Arabic [ayin, a sound linguists call a voiced pharyngeal fricative /ʕ/], and it doesn’t matter how far I push the sound into my epiglottis and twist my vocal chords, it does not sound quite right and he tells me that. He is joking but every clumsy attempt makes me trip further away, makes me more aware of the space and years and countries between us.

I don’t think I’ll ever fully know you if I don’t speak Arabic, I had once said.

Maybe it is because it is the language that his mother uses to comfort him, that he mumbles in when sleep hasn’t let him go yet, that his grandfather reads poetry in. It is the language I saw him the happiest in. English mutes him to smiles and grins, but Arabic makes him loud and outrageous, all cackling laughs and slapped thighs. He translated jokes line by line for me and I was laughing too, less because it was funny — because a joke explained never is — but because I could see his dimples no one speaking English to him could. Hidden in that divot, I could see the boy he once was in a way that photos and stories will never do justice to.

Yes, absolutely, he replied without a breath, without a pause. Of course.

Okay, I said. I’ll learn it then. Back then, I couldn’t stand the thought of any part of him being unknowable to me. Winding between the lilting letters and granite-rough sounds, there is a hollow holding the person he used to be, the one I first knew. I want to touch the dimple and push until it dents his skin in all languages, until it shows me him forever. I don’t know where he is anymore.

Learn Hindi, I said. It felt like a childish request with all the weight of an adult question. Know me, see me, love me, it chanted in a low undeniable bass. Without a breath, without a pause, he laughed and said no. It was a joke, a ridiculous request.

And I do not understand. How could you stand not knowing a part of me? Several even?

I don’t know or love that boy anymore. I haven’t spoken to him in nearly a year. But I still catch my throat contorting to make that sound, trying to get one step closer to understanding. I haven’t managed it quite yet.

In English, I am poetic I am eloquent I am sad. I have too many words to describe what I feel and I feel too much. I can’t stop scanning my mind for the perfect word that encapsulates the hyperspecific feeling, I can’t stop looking for the metaphor that holds the prettiness of my words just right. I write incessantly about dripping water and moving trains in abstract terms, wrapping up the heart of it in so much poetry that you have to squint to find me within it. I know how to use English to come off as smart or funny or, even better, both. I studied it for nearly four years and wield it like a weapon now. I am loud, I demand the attention of the room, I let myself drop like a rock in the conversation and force it to work around me. My brain is a cassette tape of scratchy noise and endless commentary and I have yet to find the end so I keep speaking, thinking, dreaming in it.

I am everything I am not in any other language.

I don’t know if my first language was Tamil or Telugu, but I know Hindi was third. I am told I was once fluent in them all. I hear stories about the wonderchild who would know exactly how to switch in all of them depending on who she was with, Telugu for her Ammama and Thathiya; Tamil for her Paati and Thatha; Hindi for her parents and for her friends. English had the antiquated formality of school work for her, and her voice takes on the up-and-down rhythm of a first grader in a reading competition when she speaks it (good-MOOR-ning TEA-cher).

I don’t know what my tell is, and I don’t have a dimple to press, but I know where she is and what words to speak to find her. She exists a little bit in all the languages.

In Hindi, I make brothers and sisters and uncles and aunties out of everyone. I am more confrontational, and the language itself is emphatic enough to let me be, but each jab has far less force behind it. I find everything funny except for me – I don’t drop like a rock into conversation, but I float in the waters around it instead. Insults are funnier, especially when they are less consequential. I am cynical and light. Politeness is a farce, but that does not mean I am not kind (the mark of closeness for us is when you can drop the act and accept the care without making a point about it with the relentless please and thank you and how are you? good thanks, you?). My brain is quieter, sometimes a humbly comedic commentary narrating things, but content to absorb the sounds of the city in the silence otherwise. There is always a baseline sense of family and love and being complete. I let myself be someone younger, someone softer, someone shyer. These are words no one would use for me otherwise.

Tamil is for my grandparents. It is measured and I am constantly thinking of how to twist the words to make sure I am including the right respect while speaking to my Paati. Have you ever heard of receptive multilingualism?1 It is when you can understand a language but have no agency over being able to speak it. It also means now that the second I say something incorrectly, I have a sense but I have no control over getting it right. It is the equivalent of seeing a puzzle and then fumbling in the dark to search for a missing piece – you think you know what shape it is missing but you have never scrutinised it enough to know in absolutes. The harder I think about it sometimes, the easier the meaning escapes me. But I continue to fumble in the dark, even if it means picking up the wrong pieces over and over again.

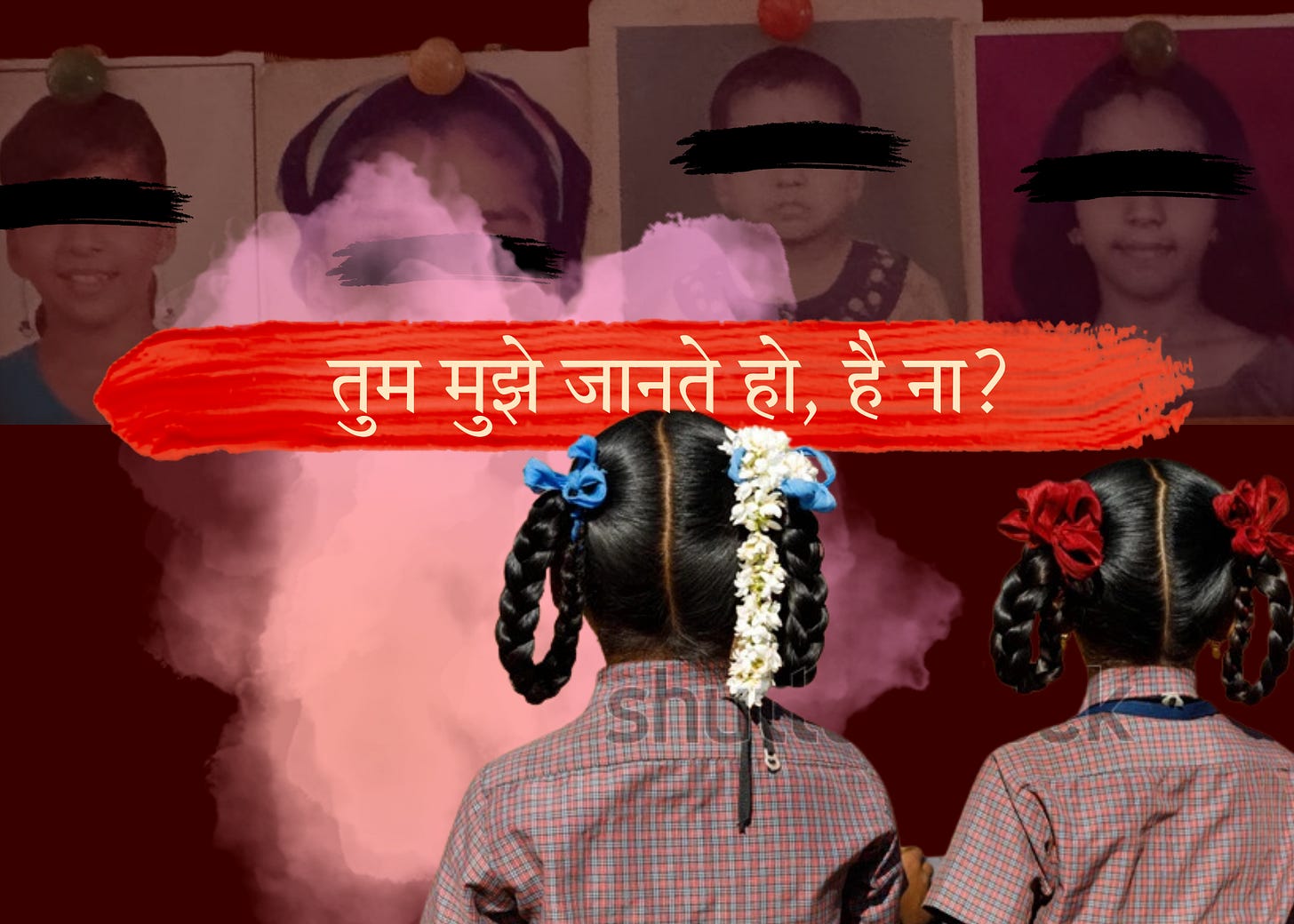

I do this because in Tamil, my grandmother tells me about her childhood in a home with more siblings and aunts and cousins than I can name. About riding on the back of someone’s cycle to go to school, about holding hands with her sisters and swinging it between them. In Tamil, I stop seeing her as someone who has perpetually been my smart and stubborn grandmother because we speak and have twin plaits down our backs, we swap Women’s Era magazines back and forth for the good stories (though I am reading all the advice columns instead), watch the worst Tamil TV serials that no one else in the family cares for. Tamil creates a bridge that stretches out and erases the generations between us and we are echoes of each other; we are friends. We are girls together.

Ma gets comfort from speaking in Telugu; it is her dimple to press. She makes up lullabies and sings us awake with it, she gossips with me in it. Even though everyone in the house can speak and understand it far better than me, I am the only one who consistently receives it. She raised me with it, scolded me with it, stopped speaking to me in it when she was told to remember she was raising a Tamil child. Languages are not just a method of communication but keepers of something far more precious and even if it is unarticulated, it is known. Languages draw harsh boundaries between places where I am from. Every time Ma speaks to me in it now, I hope she feels the ghost of rebellion because every time I understand it, I do.

I could do this for everyone in my family, you know. They speak and I see them not as the people that have been parents or grandparents in perpetuity. I see the children, the siblings, the aunts and uncles they are. I see the way they would’ve laughed in school, the games they would’ve played at home, the gentle push they would’ve given to their siblings. It’s nice to have them preserved this way, even better that I can access it.

There is a fundamental truth I believe: you will never be able to understand someone unless you speak all their languages, the ones their tongues first learned to sound, the ones that narrate the story in their heads. There is a space where you are a collection of all the people you once were and the person you continue to be and your mind and body know the words to take you there. I know this because I feel it, from the person who can speak and the one who can’t.

I think if you are lucky, you are held in its hollows forever. If you are luckier, you have someone who knows the way there, or maybe you have someone willing to learn to follow the path that led you there. Your languages know you as a child, they remember you more than you do. Unless I speak the language that your mother sings lullabies to you in and your grandfather reads poetry in, I will never fully understand and know you. And you, likewise, will never know me.

Behind-the-scenes thinking, in line with how much English gives me the language to convolute things: How do you make a snippet of a feeling into a palatable essay? How do you be vulnerable and make the point entirely about your personal experiences without drawing academia into it? How do you do it without being boring and pulling relatablity away?

But at the end of the day, these are feelings I feel and I will put words to the cassette tape still rolling with no end in sight in my head and trust that in the vastness of the world and the complexity of people, someone else’s tape is syncing with mine, if only for a moment.

How can we understand a language but not speak it? (The Swaddle)

beautiful piece !!! it's so true

god, this is breathtakingly beautiful